A Lifelong Passion For Over 40 years…

My quest to become an archaeologist began when I was very young at age 10 and has continued through the years thanks to many mentors. Archaeology made a big impression on me because construction a few miles away from our home unearthed the remains of thousands of years of occupation by the first people to live there, the Ohlone. Our home, nestled against the low, soft curves of the Santa Teresa foothills, lay in the midst of a suburban sprawl that had once been a mix of orchards and hay fields. A pastoral valley was being transformed into Silicon Valley. In the process, the past was plowed up, bulldozed, and eradicated.

Future archaeologist at work: Jim digs in with his first shovel with his grandfather Frank in Federal Way, Washington in 1962. He began his career as an archaeologist just ten years later!

The Dream Begins

My first opportunity to touch the past came at age 14. At the end of each work day, when the construction workers ended their shift, walking alone, I passed mounds of earth plowed by bulldozers, and deep trenches cut by backhoes. And as I looked closer, I realized that I was not alone. I was surrounded by the unearthed dead. An outline of golden-stained ribs and the curve of a skull protruded, fossil-like, from the sidewall of a trench. Broken stone tools, from bowl-like mortars to projectile points for spears and arrows, lay discarded in the back dirt with broken bones.

Collecting what I could, I sketched out a map in my school notebook to mark where my finds had come from, and realized that I needed to do more. As the days turned into weeks and then months, I returned daily, salvaging what I could at the end of each day when the construction workers went home. Acting boldly, I presented myself to the construction supervisor one day when I arrived before they all went home, and was rewarded with an extra set of blueprints for the new subdivision’s streets, sewers and power lines. Now I had a base map on which to plot each day’s finds. Some were isolated and meager – a single shell bead, all that remained from a necklace – while others were more complete and poignant.

My mother suffered daily with a dirt-caked, dusty son coming home and promptly disappearing in the bathroom to gently wash the finds he carried with him. She was horrified, but did not scream when she opened the door one day to see me kneeling over the family bathtub, gently scrubbing the mud from a skull. My parents worried, but were comforted by the fact that their weird child was not on drugs and was studying hard at school. They didn’t even perceptibly bat an eye when I started running around with an older crowd. That crowd included the graduate students of an archaeology class from San Jose State that I encountered digging at the construction site. They took me under their wing. I turned over all my finds to the University except the human remains I had saved from the bulldozer; they were repatriated to their descendants and reburied in a traditional ceremony.

50 Cent Per hour Museum Assistant

I passed the days and months of high school in other digs and surveys. Thanks to new laws that protected the past, archaeological surveys and excavation now had to precede construction. With local archaeologists Rob Edwards and Chester and Linda King, I happily spent weekends and afternoons walking through fields and orchards about to vanish beneath new subdivisions looking for the telltale traces of prehistoric settlements.

At this time, another mentor, Constance “Connie” Perham, founder and curator of the New Almaden Museum, entered my life. Connie, an older and wise woman, lived in a small, then isolated area outside of San Jose, the former mining town of New Almaden. North America’s greatest deposit of cinnabar (mercury ore), New Almaden flourished from the 1850s through the Second World War. When the mines closed, Connie and her late husband Doug had moved in, saved relics, collected reminiscences, rebuilt an old adobe, and in the midst of raising a family served as the caretakers of New Almaden’s past.

Connie took me in as a fifty cent per hour assistant, putting me to work sweeping the floors and washing the large picture window glass cases with vinegar, warm water and newsprint. Other tasks, eagerly accepted, included excavating and rebuilding (albeit poorly) the brick walkway that once had formed New Almaden’s sidewalk in front of Connie’s adobe. Counting on the energy but also the endless capacity of a teenage boy for boredom, Connie carefully watched from a distance as hours of sweeping and window washing were alleviated by studying every artifact and every label in the cases. Once she was sure I had learned, I graduated to tour guide. One of the many lessons she taught was that collecting the past meant nothing unless you could share it with others and make it relevant and exciting for them.

U.S. National Park Service (NPS)

At age 20, I found myself out of suburbia and in the big city when I transferred from San Jose State University to San Francisco State and joined the ranks of the U.S. National Park Service. I also found myself standing, one afternoon as I searched for an apartment, at the corner of Clay and Sansome streets in the heart of the downtown financial district. There, in the midst of a huge hole, the black-stained bones of the ship Niantic had been revealed by construction. Transfixed by the sight, the crowd of onlookers, myself included, stared at this relic of San Francisco’s Gold Rush past, unearthed amidst high-rises after a 129-year slumber beneath the landfill that buried the old waterfront.

Jason and the Argonauts, Sinbad, and Ulysses all portrayed dramatically on the screen to excited young eyes, and reading Jules Verne and Robert Louis Stevenson, had also fired my soul when young, but I thought my destiny as an archaeologist was on dry land. Niantic changed all of that. The saga of that ship, wrested out of the timbers and thousands of well-preserved artifacts found inside the hull, and the story that emerged from the archives of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, was a life-changing encounter.

Drawn by the immediacy of the ship’s story, and of the dramatic saga of the Gold Rush and the hundreds of ships that still lay buried beneath downtown San Francisco, I was hooked. The discovery of another buried ship, the whaler Lydia, a few months after Niantic’s accidental resurrection, and then the February 1979 excavation of another Gold Rush ship, William Gray, at the base of Telegraph Hill firmly set the course. At both of those buried ships, I met archaeologist Allen Pastron. Allen let me join his crew at the bottom of a deep pit that had just reached the top of the hull of William Gray. Thanks to Allen, the siren song of the sea, and the drama of a lost and buried ship now filled my archaeologist’s soul.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA)

I joined the cultural resources management team at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area as park historian at the same time as the William Gray dig. The GGNRA was then a 36,000-acre national park, euphemistically called a “national recreation area” because its urban setting was primarily intended to provide a range of locales that embodied “outstanding natural, cultural, recreational and aesthetic” values for the people of the city and visitors. My nine years in San Francisco were an intensive lesson in the documentation and preservation of historic and archaeological sites in the park.

Thanks to a supportive and mentoring boss, Doug Nadeau, I was able to stretch my job assignments into archaeology and diving. One early project was the wreck of the Gold Rush steamship Tennessee in Marin County. Our labors in the sea and the beach sands were rewarded by hundreds of artifacts that we carefully mapped and recovered. The pieces of Tennessee graphically demonstrated how the steamer had been ground into tiny pieces by the surf and spit out onto the beach after Tennessee’s captain missed the Golden Gate on the foggy morning of March 6, 1853 and crashed ashore in the cove.

I also began to work outside of GGNRA, thanks to the NPS’s growing awareness of a vast array of shipwrecks within the boundaries of national parks. Another Gold Rush steamship wreck in a national park, S.S. Winfield Scott, in southern California’s Channel Islands, led to a project to map its remains and nominate the wreck to the National Register in April 1982. In deeper, calmer water than the fragmented wreck of Tennessee, Winfield Scott nonetheless was a broken hulk buried by shifting sand. Pieces of the wooden hull peeked out of the bottom in a sea of waving kelp. Pieces of the engine, and the two paddlewheel shafts, with portions of the wheels, are the most prominent features of the wreck. Diving on the “Winnie” added to my understanding of the first steamers to navigate the Pacific Coast, and reminded me of the importance of the Gold Rush in the early history of California’s development.

But the great breakthrough into the fascinating world of shipwrecks and underwater archaeology came that same year thanks to a project up the coast in nearby Drakes Bay. The project was run by the NPS’ new Submerged Cultural Resources Unit (SCRU), a team from Santa Fe, New Mexico headed by Dan Lenihan. His team included Larry Murphy, a big, brisk and competent diving archaeologist who would become one of my best friends. Dan had single-handedly built his organization out of the apathy and outright hostility of some in the NPS who thought the agency should be doing things other than hunt for shipwrecks. The iconoclastic Lenihan and his “damn the torpedoes” attitude were just my idea of right-thinking archaeologists, and Dan and Larry became my new mentors.

From Drakes Bay to the warm waters of Pearl Harbor and the battle-ravaged remains of USS Arizona, to a wreck at the turbulent mouth of the Columbia River to the atomic bombed fleet of Bikini Atoll, with interludes in Cape Cod, and back home at GGNRA, Dan and Larry taught me how to dive wrecks and how to “do” underwater archaeology.

Philosophical discussions over the role of anthropology in underwater and maritime archaeology, as well as a strong preservationist approach to saving wrecks from the ravages of treasure hunters also formed a solid core in my education. That work also included working outside the National Parks, helping friend John Foster, California’s state underwater archaeologist, document and identify wrecks that included Gold Rush sailing ships sunk off the Sacramento’s “Old Town” on the Sacramento River, and a wreck that another good friend, wreck diver Dave Buller, had pointed out, which turned out to be a fascinating Gold Rush wreck, the clipper brig Frolic. When I took a year’s sabbatical from the NPS to go back to school and gain a Master’s in the field, I left with a solid background thanks to my friends.

Learning and Teaching at East Carolina University

My year at East Carolina University was another intensive period of study and work. A relatively new program founded by history professor William N. “Bill” Still and Gordon P. Watts, the first archaeologist to study the famous Civil War ironclad, USS Monitor, the “Program in Maritime History and Underwater Research” was one of only two schools in the U.S. to offer a graduate degree and a strong partner (and rival) to Texas A&M’s nautical archaeology program headed by George Bass, the founding father of underwater archaeology. Together, the two programs have produced the lion’s share of practicing underwater archaeologists in North America, as well as museum directors, curators and professors.

Arriving at ECU in 1984, I spent the year teaching basic U.S. history, studying, and completing a required field season’s work by surveying 60 miles of Cape Hatteras National Seashore’s beaches for shipwreck remains uncovered by seasonal erosion. With the loan of a four-wheel drive ranger patrol vehicle, and happily back in uniform for a few weeks, I surveyed dozens of wooden ships and steam engines sticking out of surf and sand with a group of fellow students, including Kevin Foster, who I would later hire to join me in the ranks of the NPS.

USS Monitor Project Historian

Just before I left North Carolina, though, came a phone call that once again represented a crossroads. Edwin C. “Ed” Bearss, the Chief Historian of the National Park Service, called from his Washington D.C. office with a simple question. As the only NPS historian with an impending graduate degree in maritime history and archaeology, and a proven track record for production (I’d written dozens of National Register nominations and studies), he wanted to know if I’d like to join an NPS team to help the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration manage the wreck of USS Monitor. I served as the project historian for the USS Monitor for the next few years, writing the study that made the wreck a National Historic Landmark. Assessing Monitor, a famous “icon” shipwreck, was a revealing look at why people think certain things are “historic” and worth saving.

As an archaeologist, I was, on one hand, disdainful of just studying “big name,” famous wrecks, arguing that the unknown, workaday ships (the floating equivalent of the “man on the street”) were more deserving of study as they were more indicative of the common experience at sea. But the how and why some ships become “famous” was in itself a compelling area of study. Today, as an archaeologist who has visited and studied a wide range of famous ships – USS Arizona, USS Monitor, Titanic, Carpathia, Mary Celeste, Somers, and many others, I find the noteworthy and notorious to be yet another archaeological window into the human soul.

National Maritime Initiative (NMI)

The work on USS Monitor led to a new assignment for Ed Bearss. In early 1987, Ed tapped me to run a new program Congress had tasked the NPS with. Known as the “National Maritime Initiative,” the job was essentially to create a national maritime preservation program for the US government. Inventorying every known historic maritime resource, from floating ships and shipwrecks to lighthouses and shipyards, developing standards for their preservation and restoration, assigning priorities for preservation, and “appropriate roles” for the government and the private sector filled the next four years.

The NMI years were the most intensive years of learning in my life. It was like a graduate level program in maritime history, archaeology, preservation and interpretation. I was hardly ever in Washington. I spent nine months of each year in the field, visiting nearly every one some 330 historic ships in the United States, climbing up hundreds of lighthouse towers, visiting shipyards and naval facilities, and diving wrecks. I went to nearly every maritime museum and library in the country, and visited others abroad in Canada and Britain.

My time in the NPS also included an annual summer expedition with Lenihan and Murphy on a shipwreck project. Dives on the storm-ravaged square-rigger Avanti at Fort Jefferson, in Florida’s Dry Tortugas near Key West, as well as work at Pearl Harbor to study USS Arizona and USS Utah and to search for crashed Japanese aircraft and sunken midget submarines from the December 5, 1941 attack filled some summers. Two years of field work at Bikini, 9,000 miles from Washington in the heart of the Pacific, brought the team face to face with the results of nuclear testing as we dived into the graveyard of a fleet sunk by the atomic bomb. I spent my last field season in 1990 leading a team to Mexico to jointly study the remains of the 1846 US brig Somers, a project introduced to me and the NPS by my friend George Belcher of San Francisco, who had discovered the wreck.

San Francisco Gold Rush Ships

During my 13 years in the National Park Service, I had remained active as an archaeologist outside of the National Park System thanks to friends like George who involved me in their projects. My very good friend, Allen Pastron, who runs a consulting firm of archaeologists named Archeo-Tec nearly single-handedly excavated much of downtown San Francisco’s great sites. Thanks to Allen, I had joined the crew digging up the ship William Gray in 1979, and later returned to the field with him to unearth a Gold Rush store that burned and collapsed into the bay in 1851, a shipyard where old Gold Rush ships were dismantled between 1854 and 1857, and a sailor’s boarding house that burned in the 1906 earthquake and fire. In 2001, we excavated another site just like Niantic. That ship, General Harrison, lay only a block away from Niantic’s grave. It was a wonderful opportunity to return to San Francisco and help unearth another ghostly relic from the days of the Gold Rush in the heart of the city. It was also, literally a return to my roots as a maritime archaeologist. It also served as the subject of a long-delayed Ph.D. dissertation at Simon Fraser University.

Vancouver Maritime Museum (VMM)

In early 1991, with every task Congress had set before the National Park Service as part of the challenge that formed the National Maritime Initiative completed, I left the NPS. The years of travel had left a yearning to find one place, one museum, ship, or shipwreck to focus on. The opportunity to return to the Pacific Coast and to live in Canada’s great port of Vancouver as director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum lured me out of government service.

For 15 years I worked with a great team of trustees, staff and volunteers at the Vancouver Maritime Museum. That included organizing a $3-million reenactment of the historic Northwest Passage and North America circumnavigating voyages of the museum’s centerpiece exhibit, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police schooner St. Roch. It also included the rescue and reconstruction of the historic oceanographic research submersible PX-15, Ben Franklin. Having been in a small museum gave me the freedom to be hands-on, not just in the research and the exhibits and programs, but with the projects. Serving as a member of the crew of the St. Roch II Voyage of Rediscovery meant visiting Arctic ports and connecting with people who remembered the original ship and its crew. Restoring Ben Franklin meant working with crane operators and a volunteer to reassemble the sub a piece at a time, bolting and hammering two storeys up, hoping to God that I didn’t fall.

The Sea Hunters TV Documentary Series

The last six years in Vancouver also introduced me more completely to the world of documentary television thanks to John Davis, producer of the National Geographic International television series, The Sea Hunters. Working with John, co-host and famous novelist, raconteur and shipwreck hunter Clive Cussler, master diver Mike Fletcher, his diving son Warren, and a great crew behind the camera has brought new adventures, “in search of famous shipwrecks.” We traveled the world for several seasons, meeting colleagues, diving on amazing wrecks, and sharing their stories with millions of viewers around the world.

Jim with colleagues David Alberg, David Krop, Anna Gibson Holloway and Larrie Ferreiro at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC after presenting an all day symposium on the wreck of USS Monitor

Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA)

I left the Vancouver Maritime Museum in 2006, just as the Sea Hunters concluded its final season, because a new opportunity had come thanks to George Bass, the father of underwater archaeology, and several directors of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology. That opportunity was the position of executive director of INA, a job that involved me in making a difference for INA in the areas of fundraising, development, marketing, project development and strategic planning. In 2008, the INA board selected me to become INA’s President and CEO, a job that I took to heart. It meant extensive travel, especially to the various countries where INA works, creating new relationships, reaffirming old ones, and implementing INA’s new strategic plan, which the board twice reviewed and unanimously passed in 2008 and 2009. I made some incredible friends, learned a great deal, raised more than $3 million for INA and Texas A&M University, and was able to make a difference as INA’s “agent of change.”

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The National Marine Sanctuaries are a precious part of America’s cultural and natural legacy, and joining the team in the Fall of 2010, made me part of a new family of collegial, focused public servants working with limited resources to be effective in ocean conservation. I was proud and pleased to return to public service, and to continue to work on and in the water in this fourth decade of my career. The opportunity to work again in a nationwide system of marine protected areas but also be a part of the larger NOAA family was a key part of the profound honor to again be a civil servant. As the director of NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program, I closely interacted with the Office of Ocean Exploration, the Weather Service, the Office of Coast Survey, and other parts of NOAA. Collaborating with the team, we developed and implemented a new strategic plan, while working closely with counsel on the legal aspects of Titanic and NOAA’s role in executive branch oversight for the wreck. The program also implemented new guidelines for consultation with tribes and other Indigenous groups, introduced maritime cultural landscapes as a policy template, and created a NOAA MHP publication series.

I was proud to join my colleagues on missions and to lead some of them in California, Hawaii and abroad in Bermuda, where we rescued a storm-exposed Civil War cargo of contraband goods from the blockade runner Mary Celestia. It was also an honor to be selected to represent the United States as head of delegation in UNESCO meetings in Peru, France, and Belgium, and to be a lead policy negotiator for NOAA in diplomatic meetings in Washington, DC with Spain, France, and Germany on reciprocity in management and protection of each nation’s sunken military craft in each other’s waters.

The major projects and the wrecks we encountered included deep-water 19th century shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico, the maritime cultural landscape of Northern California’s Sonoma coast, and a three-year mission in Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary that discovered and documented significant shipwrecks; that mission led to the discovery and identification of the wreck of USS Conestoga, a navy tug that disappeared mysteriously with all hands; we were able to close that cold case and bring comfort and closure to the families nearly a century after that loss.

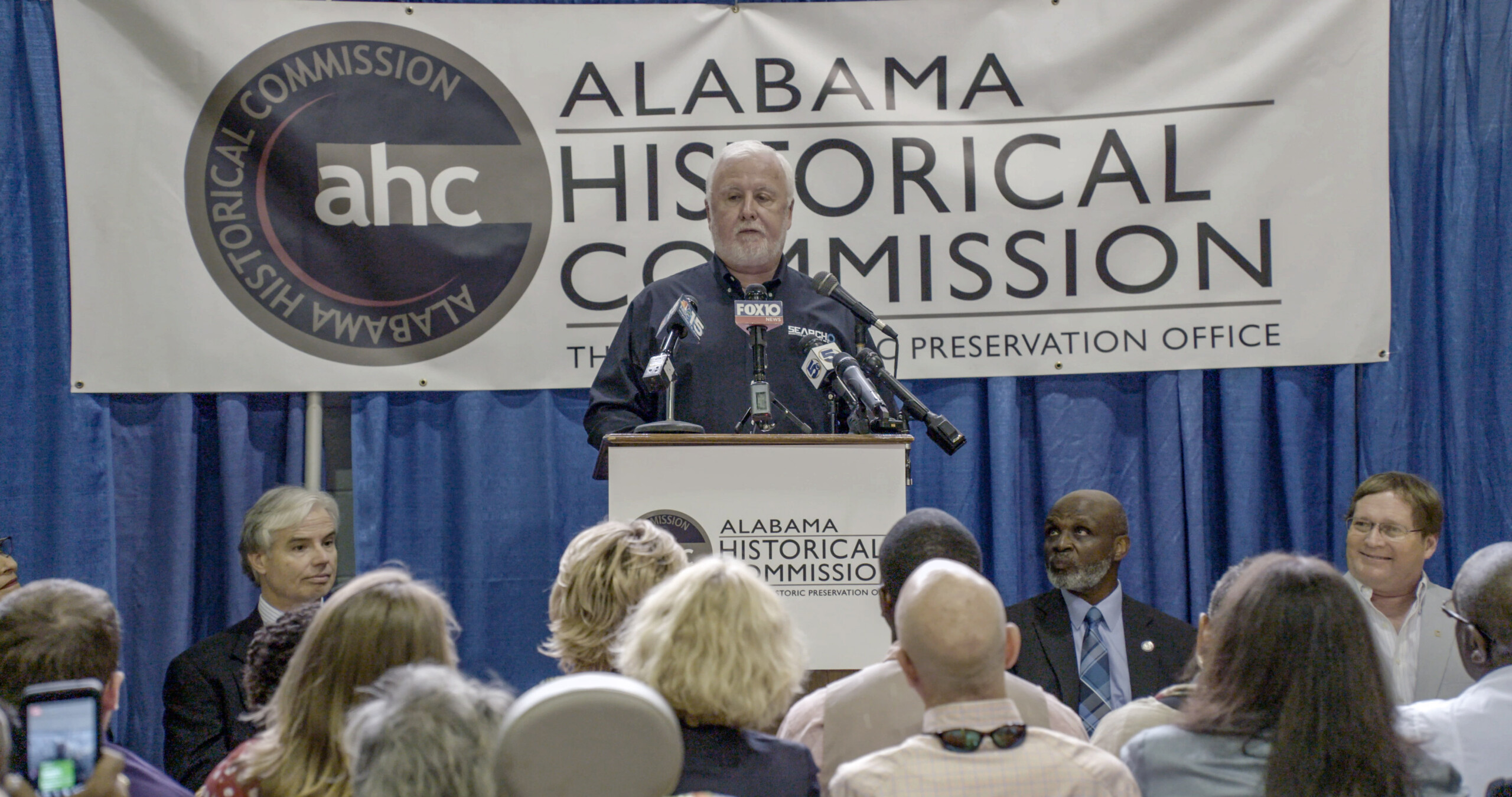

SEARCH Inc

In May 2017, I joined SEARCH, Inc. as Senior Vice President and as the leader of SEARCH’s Exploration Sector. Soon after joining, the opportunity to lead the project that led to the successful archaeological identification of Clotilda, the last ship known to have brought captives from Africa for the purposes of enslavement, with support from the National Geographic Society, and extensive media coverage from 2018-2024, including multiple documentary films, national and international news stories, and the National Register listing for and the ongoing protection and preservation of the wreck. The most profound aspect has been working with the community of Africatown and the Clotilda descendants.

With my colleague Dr. Michael Brennan, we were able to introduce SEARCH and its archaeologists to the world of oceanic missions of deep sea exploration and discovery, including the discovery of the battleship USS Nevada, the destroyer ex-USS Stewart, and multiple 19th century wrecks in the Gulf of Mexico. I was also able to continue and expand my role as a co-creator of National Geographic’s “Drain the Oceans.”

Of the many projects that have spanned the last eight years, in addition to working in the field – be it helping lead the rescue excavation of a 19th century fishing boat buried under landfill on the waterfront of St. Augustine, Florida, or preparing a comprehensive overview and a large-scale National Register of Historic Places nomination for the 19th century shipwrecks of the Gulf of Mexico, to the documentation and rescue of artifacts from the ill-fated historic ship Falls of Clyde, the architectural and archaeological documentation of the remains of the CSS Jackson at the National Naval Museum of the Civil War in Columbus, Georgia, or serving as an expert witness in shipwreck cases, to a comprehensive maritime archaeological survey and the rescue of shipwreck timbers from the wreck of Santo Cristo de Burgos, the wreck that inspired the 1980s popular film “The Goonies” it has been an amazing and public-facing near decade.

But in other arenas, it has been an opportunity to work with an exceptionally talented group of colleagues, including younger colleagues I have been able to pass some things along, and who have also taught me amazing and positive things. You are never too old to learn. Also, it has been a time for publishing both popular books, as well as scholarly ones, and maintaining a commitment to academic publication of the results of field work, including being able to circle back and close the loop on projects past with updated publications. It has also been a pleasure, with Michael Brennan, to inaugurate SEARCH’s for now unique role in representing and analyzing the cultural significance of deep sea offshore areas in the North and South Pacific, along the sea routes of the Middle Passage from Africa to Europe and South and North America, and most recently the Blake Plateau off the Southeastern United States, and publishing those studies in open-access academic journals.

The Exploration Continues

Why do I love what I do? Because the greatest museum of all is the sea. The record of humanity’s achievements, its triumphs and tragedies, rest on the seabed. My drive to see and touch the past and share it with others that began for me over four decades ago continues, thanks to friends and colleagues who join me in the ongoing quest. What I’ve learned along the way from the dead ships, both the unknown and the famous, is that they do tell their tales. Sometimes their broken bones tell me who they are and how they died. Sometimes the story of their birth, their careers, and the personalities who sailed in them also come to light, resurrected from the darkness of the deep. It is for these reasons that I keep exploring.

Jim speaking at the memorial service for the crew of USS Conestoga at the National Naval memorial in Washington, D.C. (NOAA)

Jim holding up a rigging block from the "Beeswax Wreck," Santo Cristo de Burgos, at the Columbia River Maritime Museum (James Delgado)

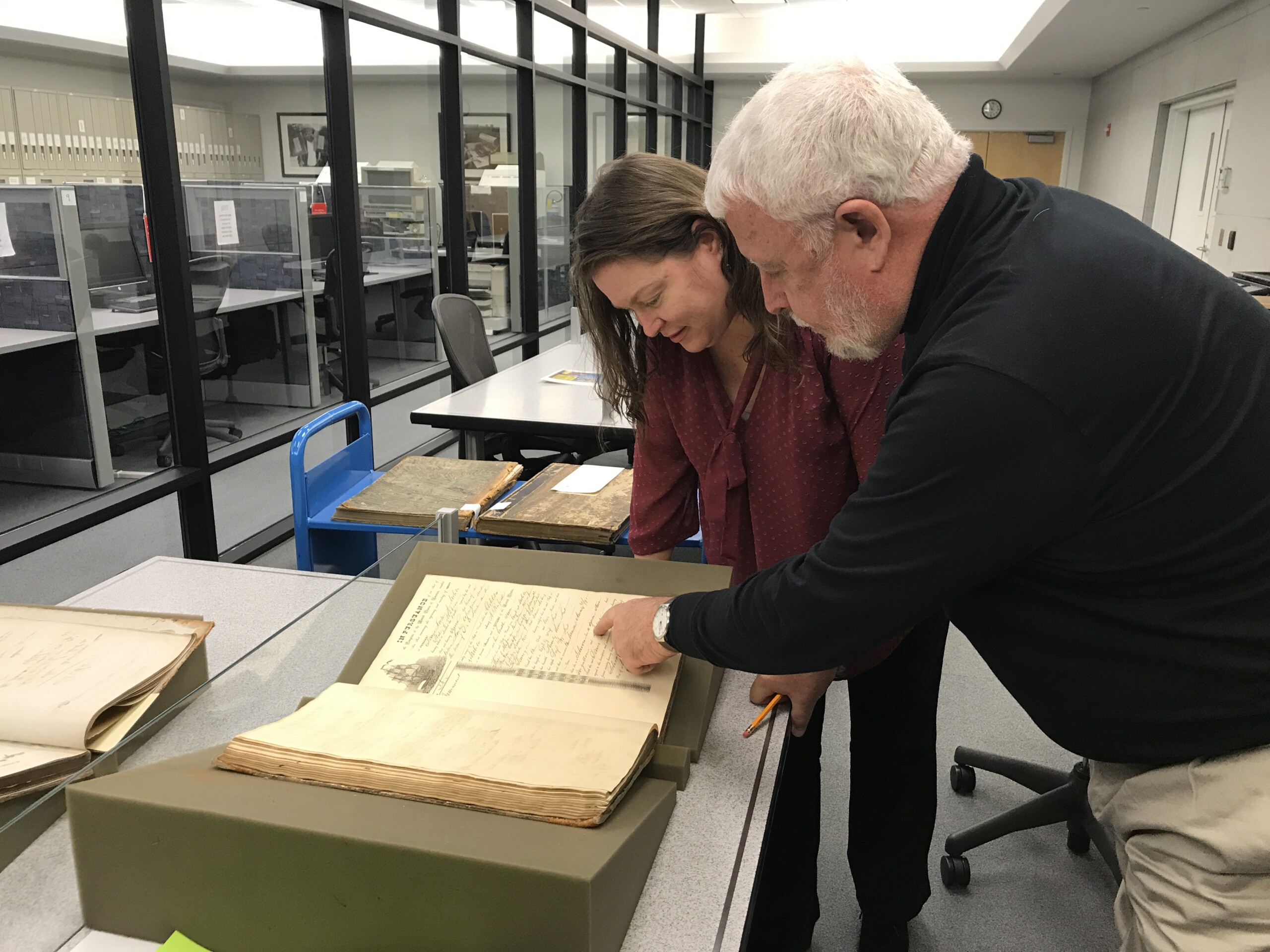

Alabama State Archaeologist Stacye Hathorn and Jim examine Clotilda’s original registery documents at the National Archives

Jim and Ariel Cathers mapping a doghole port's archaeological remains on the California coast during the NOAA/California State Parks survey (California State Parks)